Learning at Sheringham Museum

Welcome to Sheringham Museum, we hope to intrigue and inspire you!

As you may already know, Sheringham has a history going back a very long way. Some of the objects in our collection are many thousnds of years old, but the important growth in the town’s history has occurred in the last two centuries.

We have some pages here to introduce you to aspects of life in the town over those two hundred years. First, we have a few suggestions for you on how to look at the information and ask the sorts of questions that – when you have the answers – give you a better understanding of the subject. In other words, become a ‘museum detective’! Boatbuilding and the fishing industry are obvious subjects to be covered but we are not ignoring those prehistoric periods. Join geologist Martin Warren and travel back in time to discover the secrets of the cliffs, investigate fossils on the beach and learn more about flints and the chalk reef.

We are working to broaden the range of topics available to you, so we suggest you return regularly to these pages.

Be a Museum Detective

Boat building in Sheringham

Tales of the sea

Deep History Coast

Sheringham Lifeboats

Renewable Energy

How to be a museum detective

Boat-building in Sheringham

The history

Nearly two hundred years ago, a Sheringham carpenter agreed to build a boat for a local fisherman. It was such a good boat that he was asked to build more, and soon Sheringham had a thriving boat-building community, with several builders providing boats for fishermen along the coast.

Can you imagine what it was like to build a wooden boat 100 years ago? There were no electric tools so every piece of wood had to be cut and shaped by hand. Sheringham had two boatyards, but we’re going to explore the Emery Boatyard.

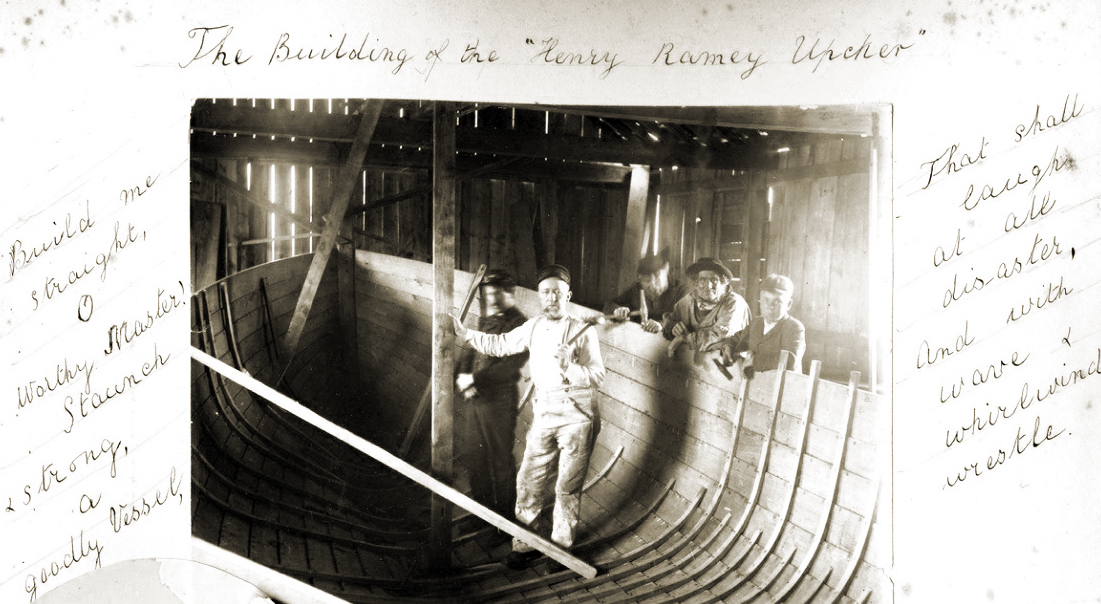

Fishermen in Sheringham often had nicknames and it was Lewis ‘Bull’ Emery that set up the Emery boatyard. He was called ‘Bull’ because he was very strong. Along with his sons he built the Henry Ramey Upcher lifeboat as well as many fishing boats. Here we see them at work.

Emery Boat Shed

This is the Emery boat-building shed as it was. It faces onto Lifeboat Plain in Sheringham – just across from the Museum.

If you look carefully you will see the end of a boat peeking out of the top level of the shed; they could build two at once!

But how did they get the boats, especially the top one, into the sea?

That’s a puzzle for you detectives to solve.

Watch the Video

The boatbuilders used different types of wood like oak and larch. It would take boatbuilders about six months to build a boat like the Enterprise. Three men would work on a boat, laying the keel first of all and then adding the stem and stern posts. They would then put on the planking which was steamed to shape and then the ribs of the boat were added, fixed in with copper nails. Boats were painted on the outside and tarred inside to make them watertight.

There were no power tools, of course, but the old boatbuilders crafted beautiful results with a variety of hand tools and, of course, a lot of skill.

Activity

Draw a boat!

Here are some old photographs of boats built in Sheringham.

See if you can draw a boat like one of these and give it a great name!.

Tales of the sea around Sheringham

Fishing

For hundreds of years Sheringham men and women have made a living from the sea.

When the weather was good or when the weather was bad they would set sail.

Fishermen used long lines and lobster pots, crab pots and whelk pots.

Fishing was hard and exhausting work. If a fisherman went to sea and there was no wind then they would have to row their boat, sometimes covering over 26 miles.

Rules and regulations

There are many rules regulations that fishermen must observe.

The types of fish and crustaceans they can catch, as well as their minimum sizes, are carefull controlled, so that our fishing stocks are preserved. Click on the video on the left to investigate further.

A Marine Conservation Zone has been declared along the length of the Cromer Shoal Chalk Bed, which stretches between Weybourne and Happisburgh. This very sensitive area is having problems – you might like to investigate!

Activity

‘Fishy Tales’ (Write a story)

Fishermen often tell tales of some of the adventures they have at sea. Watch this video to see some of the words that you can use to describe the sea. You can use them in a story.

Your ‘fishy tale’ might be about being out in a crab boat on a stormy sea, or perhaps a story about catching something surprising!

Time to start writing! Watch this video for words that you might like to use.

Deep History Coast

Nature’s Time Machine

Norfolk has 100 miles of coastline. We can all enjoy the glorious beaches with their sandy cliffs but how many of us stop and think about the fascinating stories those beaches and cliffs can tell?

What is the Deep History Coast? North Norfolk’s Deep History Coast is the 22-mile stretch between Weybourne and Cart Gap. It has sandy beaches, rock pools, chalk banks, miles of flint stones and is edged by cliffs. Full of fossils and flints and mammoth bones, the beaches and cliffs can take you back to a time when Sheringham was under sheets of ice.

Local Geologist, Martin Warren, will take you on a journey in time along the Deep History Coast. You can find out about fossils, flints and the amazing Chalk reef.

Enjoy!

Fossils

What are fossils?

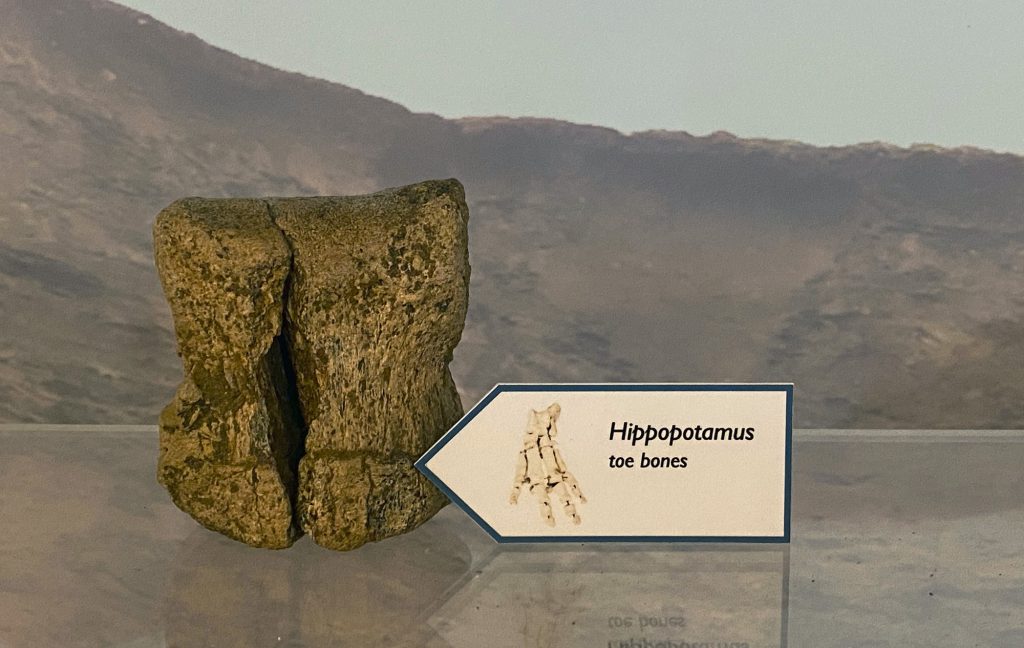

Fossils are the remains or traces of animals and plants from past geological ages. They may be bones, shells, pollen or even footprints of dinosaurs. The fossils maybe as large as a mammoth or so small you need a microscope to see them.

Along the North Norfolk Coast you may find fragments of mammoth bones, tusks and even teeth.

How are fossils made?

Fossils are often described as parts of living things which died long ago. It takes a long time to make a fossil. So how is a fossil made?

They are often formed after a dead animal/plant/fish is buried under mud or silt. Gradually more layers of sediment form and put lots of weight and pressure onto the remains. Eventually the remains turn to rock or stone, but this process can take millions of years.

Famous Fossils

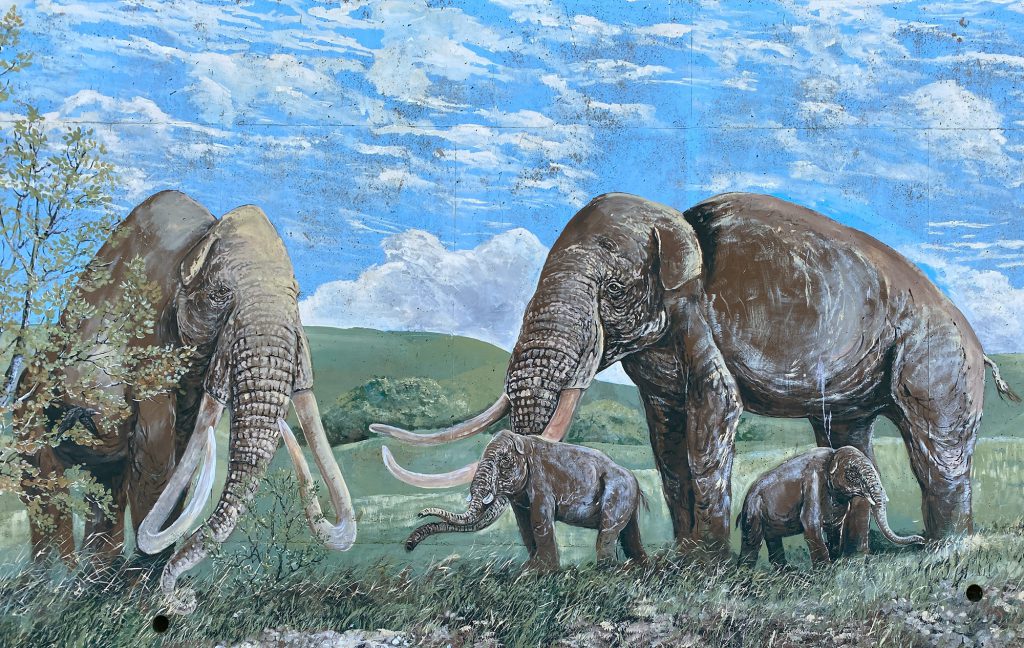

The most famous fossil found on the North Norfolk Coast is the Runton Elephant which is the fossil skeleton of a Steppe mammoth that roamed over North Norfolk around 750,000 years ago.

The mammoth probably fell into a swamp and was then covered by sediments like sand and clay.

Fossils you can find

There are lots of smaller fossils that you can find on our beaches. There are belemnites, sponges and ammonites, and much smaller fossils like the microscopic coccoliths. Coccoliths are shells of animals that make up the bulk of the Chalk strata we see exposed at low-tide and they are in some of our cliffs too.

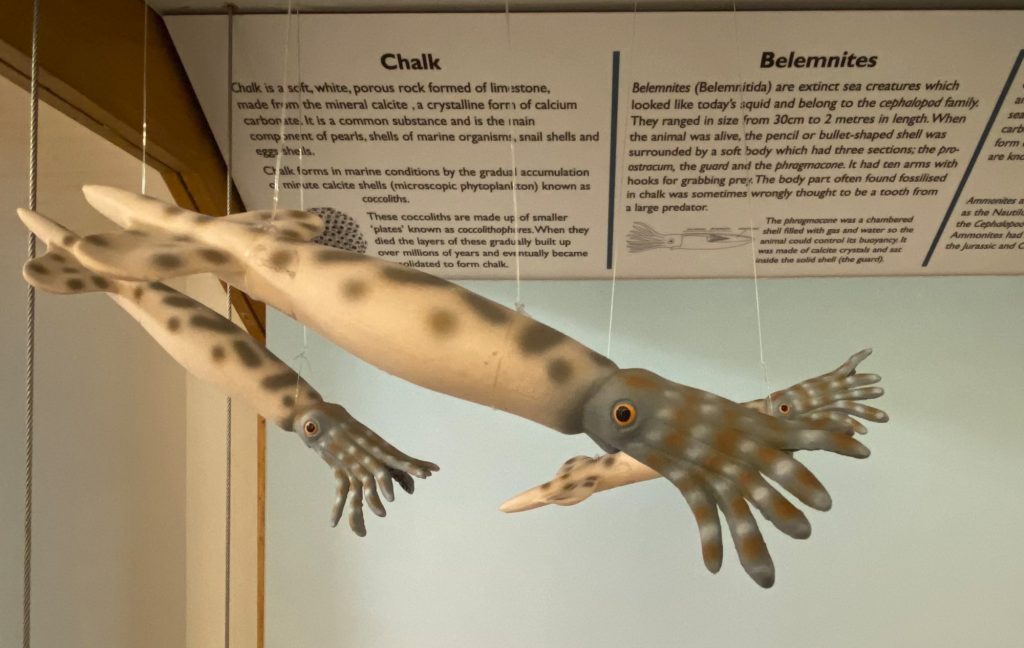

Belemnites

Belemnites look like bullets, and they are the hard parts of a squid-like animal.

They lived in the warm seas of the Cretaceous Period, when the Chalk was deposited. Like dinosaurs, they are now extinct .

Ammonites

Ammonites look like coiled worms or snakes. They are also fossils of extinct animals that lived in the warm shallow seas off the Cretaceous Period, and they are related to our modern squids, octopuses, snails and slugs.

They range in size from a few millimetres in diameter to the size of a tall person (1.8m), but the ones we find on our beaches are usually pebble-size

Sponges

Sponges are animals not plants, and we can find sponge fossils of various shapes and sizes on our beaches. Look at the picture of fossil sponges and think of words that describe their shapes.

Unlike belemnites and ammonites, sponges are not extinct, and we still use them today in the bath.

Paramoudras

On our beaches, especially at West Runton are pot stones or ‘paramoudras’. These are large flint formations with a vertical hole in the middle.

The term ‘paramoudra’ was first used in 1817, possibly a corruption of a Gaelic name, maybe ‘padhramoudra’ which means ‘ugly Paddies’ or ‘peura muireach’, – ‘sea pears’.

Some palaeontologists think they were formed by animals burrowing on the sea-bed, others think they were sponges, no-one knows for certain. Have you any ideas?

The Missing Years

If the chalk is around 70 million years old, and the layer above it is only around two million years old, why is there no evidence of the intervening years? Our next video offers some information.

Flints and the Chalk Reef

Seawater contains many things dissolved in it. Salt, of course, is by far the commonest mineral in seawater, but there is also iron, calcium and silica for example in much smaller amounts.

Some animals like fish and corals and crabs extract the calcium from the sea, and concentrate it to make bones and shells, whereas others like sponges extract and concentrate the silica to make their skeletons.

Flint is the glass-like material which originally came from sponge spicules, tiny structures that make up the sponge skeleton.

Flint Knapping

Flint is made from silicon, the second most common element on Earth. Flint can be found in a variety of shapes and sizes, ranging from small pebbles to large stones and even thick sheets.

Flint knapping is the traditional skill of making stone tools. In the distant past hunter-gatherers relied on this amazing skill to make their tools and hunting implements.

Flint is useful in other ways, and we still use it today. You will see lots of flint walls in and around Norfolk.

Sheringham Lifeboats

Lifeboats

Have you ever had a ride in a fast boat? Our inshore lifeboat has a top speed of 35 knots – that’s a little over 40 mph – and it can be quite exciting, though it’s not so comfortable when the sea is rough. This video shows what it’s like on a good day – enjoy!

Seafaring can be a very dangerous job, so for more than 180 years Sheringham has had lifeboats ready to rescue those who are in trouble at sea.

The Augusta was the first of Sheringham’s lifeboats and was launched in 1838. Then came the Henry Ramey Upcher. Both of these were privately funded vessels.

To find out more about the history of the lifeboats, what a lifeboatman might wear and to hear an exciting tale of a lifeboat rescue read on below.

The Royal National Lifeboat Institution has provided seven lifeboats over the years. In order, they have been the Duncan, the William Bennet, the JC Madge, the Forester’s Centenary, the Manchester Unity of Oddfellows and the inshore rigid inflatible boats, the Atlantic 75 ‘Manchester Unity of Oddfellows’ and the Atlantic 85 (also named ‘Manchester Unity of Oddfellows’) which is currently in service.

Sheringham’s Lifeboats

Here’s a video to introduce you to Sheringham’s lifeboats. The town has had eight lifeboats over the last 185 years, and we have five of them in our collection.

Four are on show in the museum and the fifth is housed in the Fishermen’s Heritage Centre several hundred metres west along the beachfront.

This is the best local collection in the UK and naturally we are very proud of it!

After this video you can select each of the eight lifeboats and get more information about them.

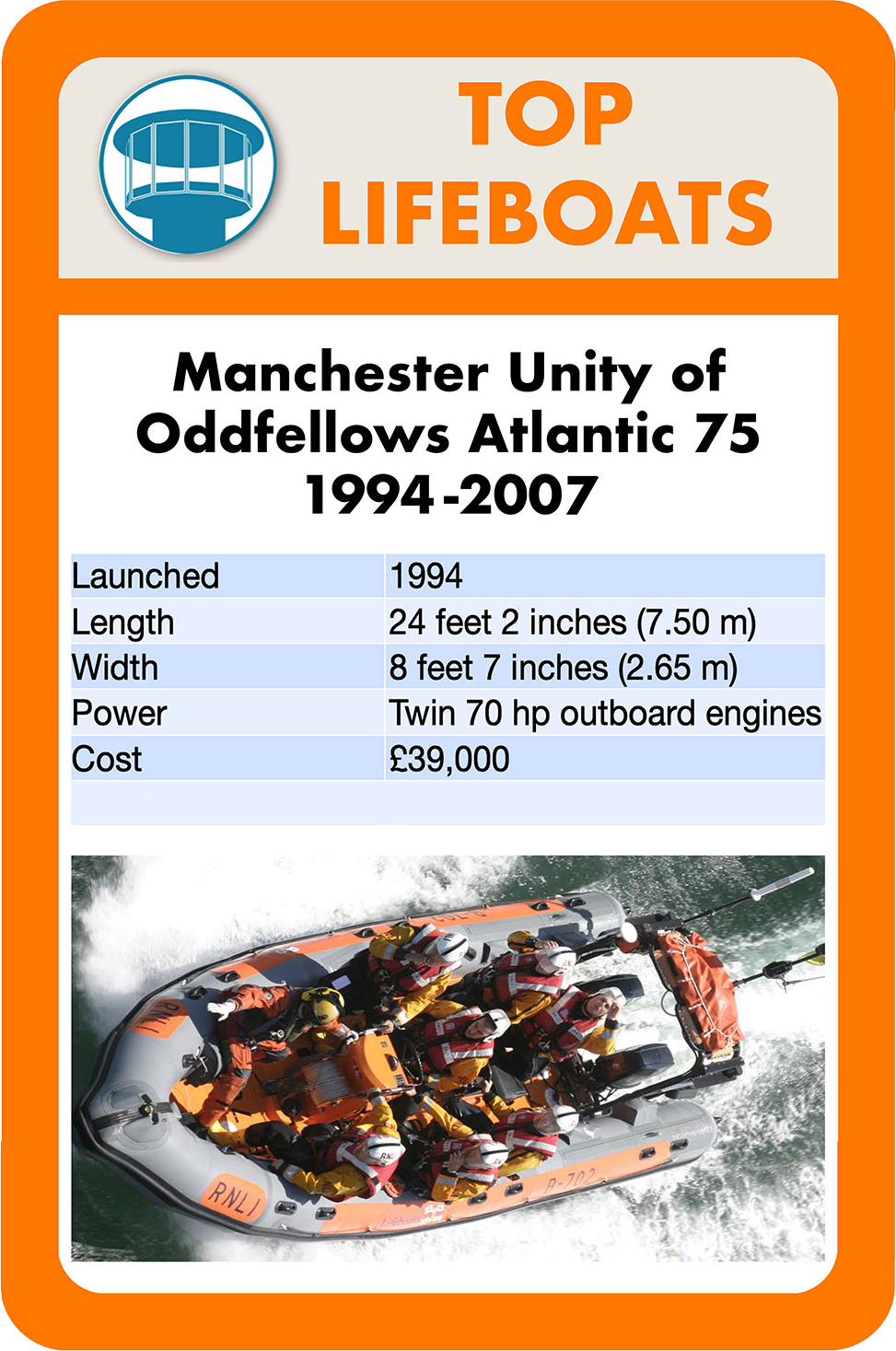

Top Lifeboats

Here you can see each of the eight Sheringham lifeboats and get more information about them.

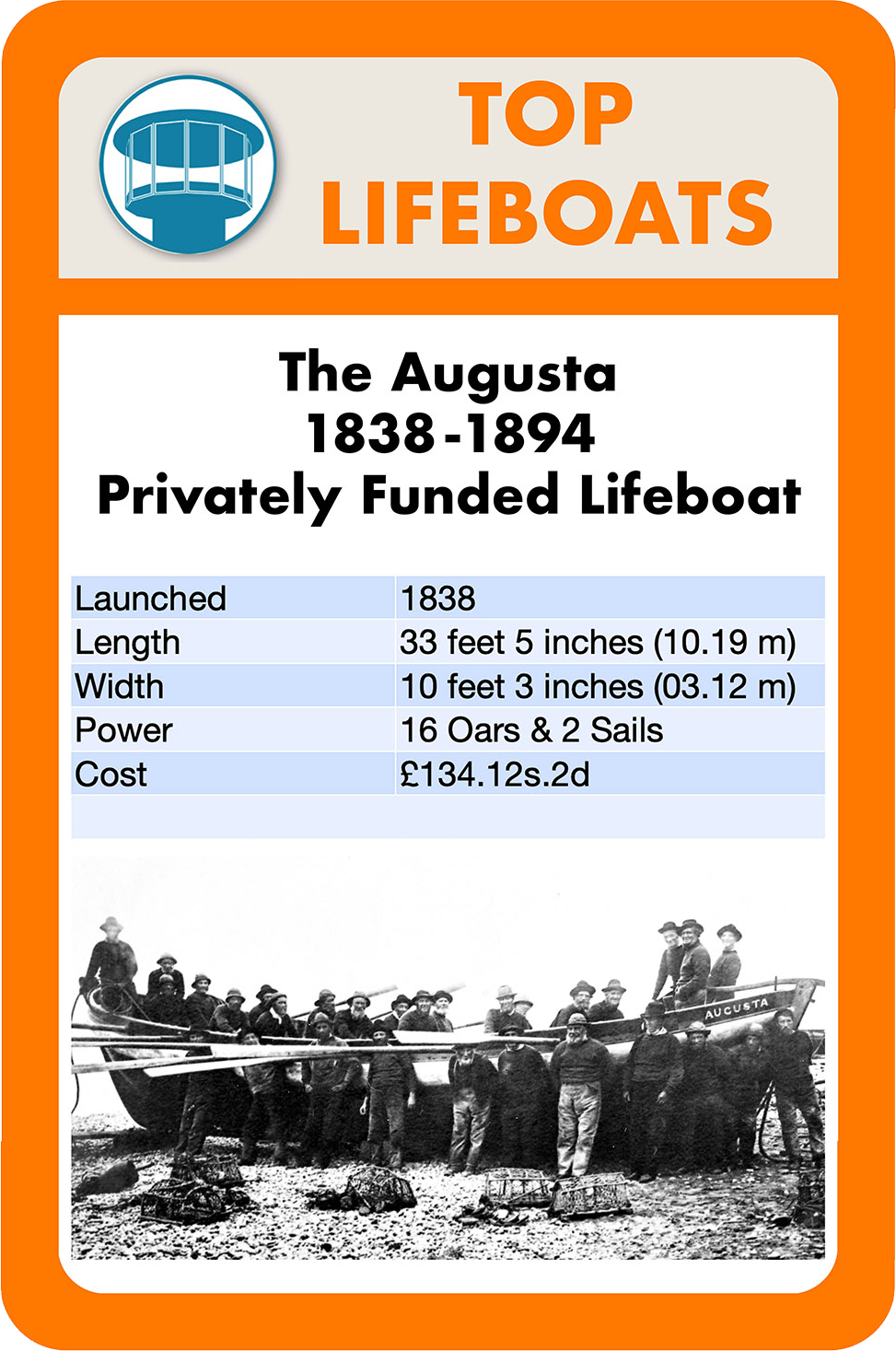

The Augusta

1838-1894

The Augusta was built just like a large crab boat. She had two pointed ends, 2 sails and 2 rudders which meant she could be steered from either end in heavy seas.

The Upcher family from Sheringham Hall donated the money for the first lifeboat, and the Augusta was named after Charlotte Upcher’s youngest child.

We think she launched at least 16 times and saved 200 lives. She was probably kept in the shed that now houses the Henry Ramey Upcher, just west of the Museum along the prom.

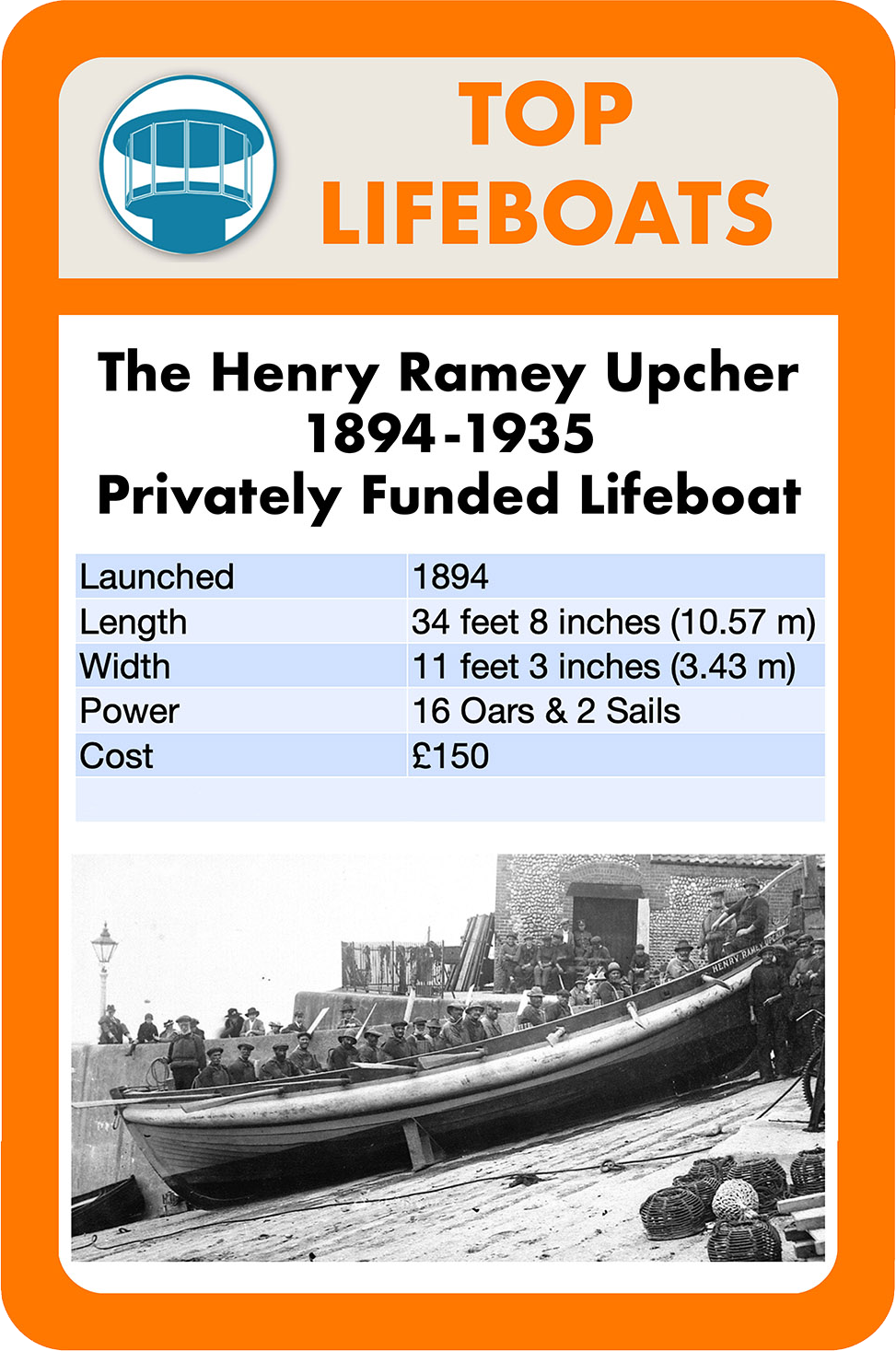

The Henry Ramey Upcher

1894-1935

The Henry Ramey Upcher was the second private lifeboat given to the people of Sheringham by the Upcher family. Mrs Caroline Upcher named her after her husband, who had died. She was built by Lewis ‘Buffalo’ Emery and, like the Augusta, she had 16 oars.

She was a well designed boat because she was very light so she was easier and faster to launch, and not only did she save the fishermen, but she often saved their gear and boats.

The Henry Ramey Upcher was in service until 1935 so she worked closely with the heavier RNLI boats, the William Bennett and the J.C. Madge. However she shipped water more easily so the RNLI boats worked better in heavy seas.

With a crew of 28, she launched 50 times and saved over 200 lives. You can still visit her today in her shed at the top of the fishermen’s slope.

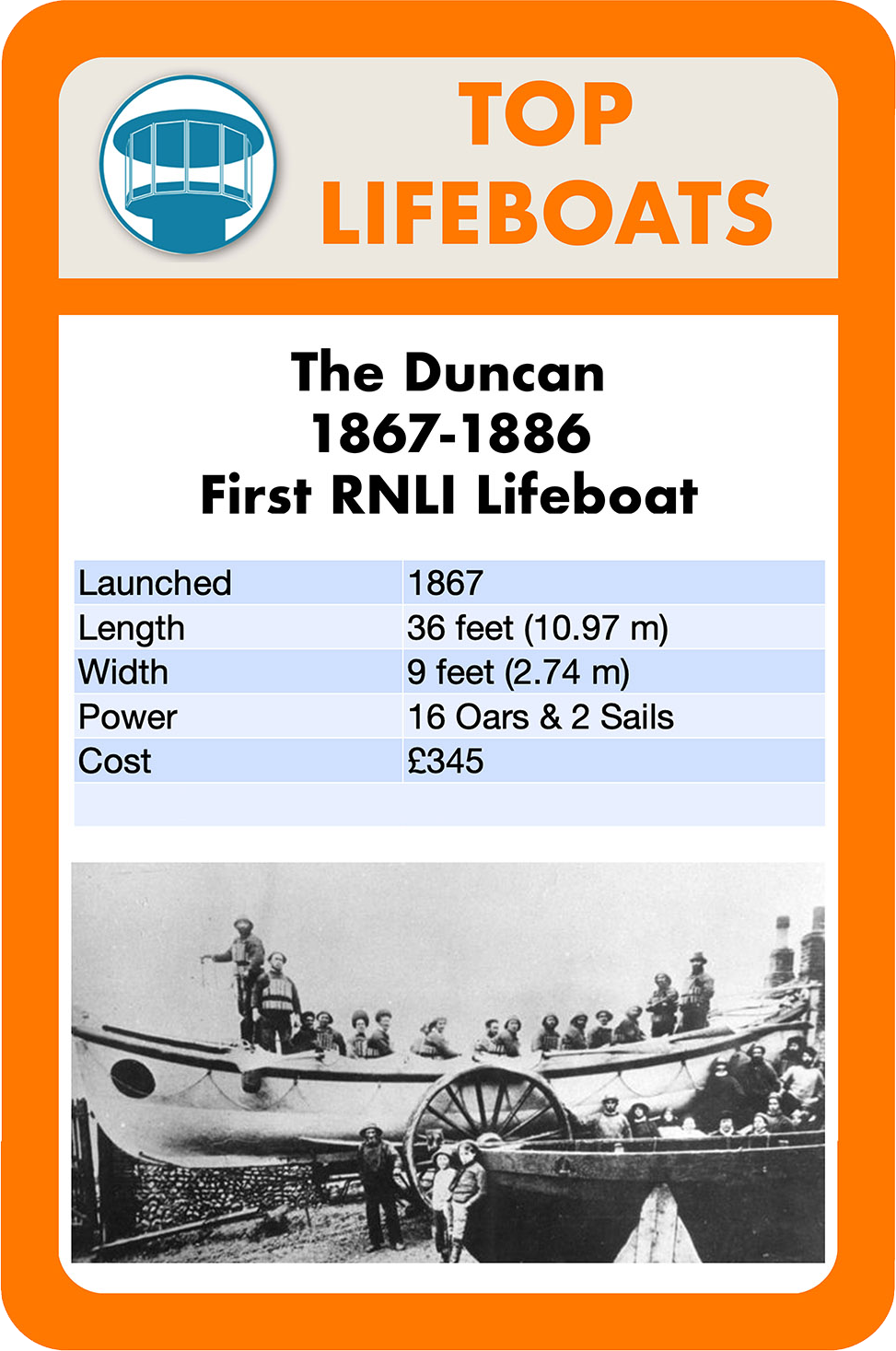

The Duncan

1867-1886

The Duncan was the first RNLI lifeboat in Sheringham and she was housed in the newly built Lifeboat station. Her home was what is now the Oddfellows Hall on Lifeboat Plain, behind the Crown Pub.

She was 36 feet long and 9 feet wide. She was built in Limehouse, London, and came by rail to Fakenham and then by road on her carriage all the way to Sheringham.

In her 19 years in Sheringham, she launched 7 times and saved 18 lives. The Duncan’s first successful rescue took place on 3rd December, 1867. She saved the crew of the schooner ‘Hero”. Later lifeboats had to be housed in a more safe position because storms washed away the slipway several times.

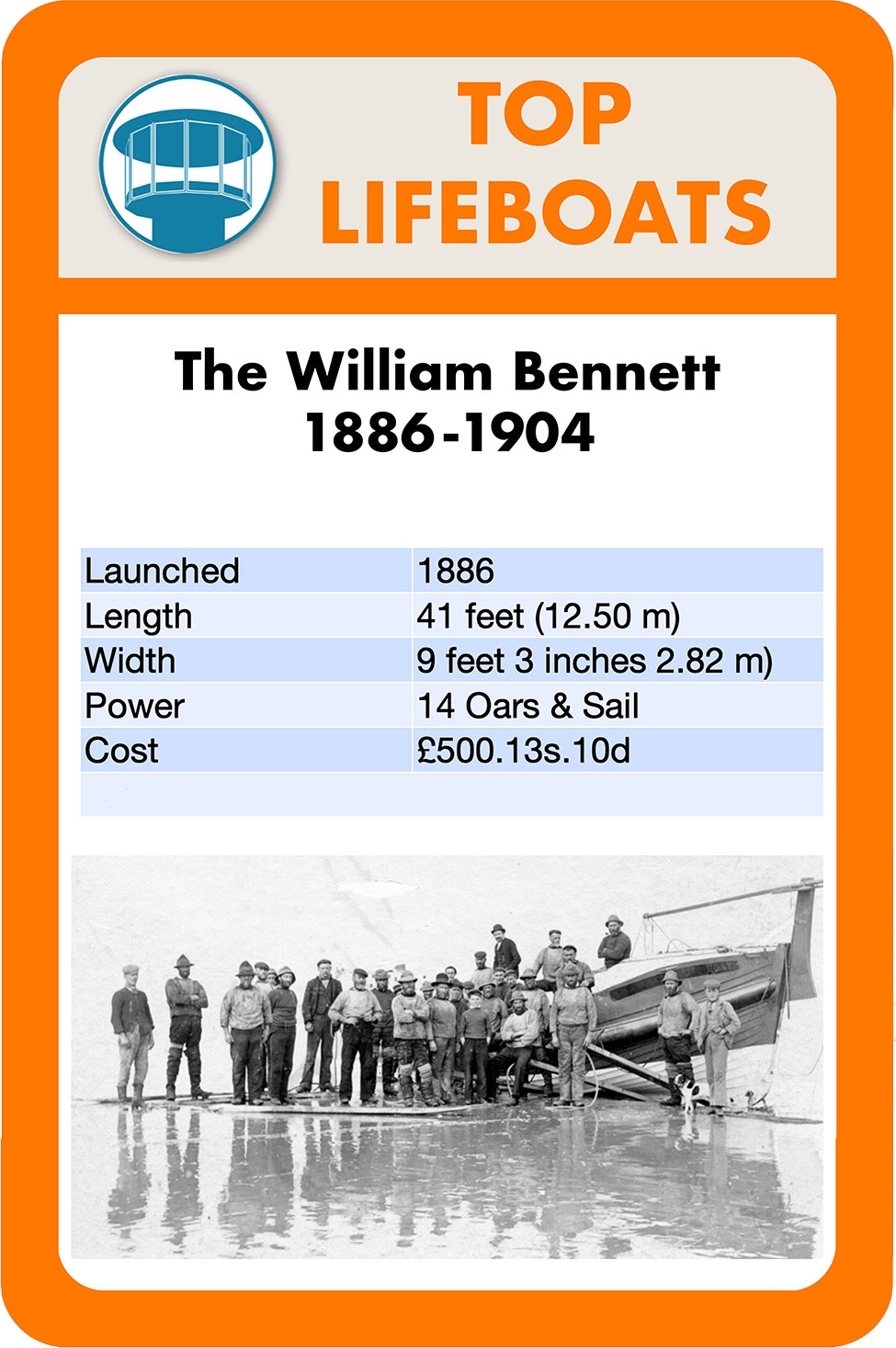

The William Bennett

1886-1904

This lifeboat was actually the first to arrive in Sheringham by sea! She was 41 feet long and 9 feet wide and had 14 oars and she was self righting, and cost £500.

Being much heavier than the Duncan and much harder to launch, she only launched properly 4 times, saving 11 lives. Much of her work was to help the Augusta & the Henry Ramey Upcher to assist fishing boats in trouble.

Her first successful launch took place on the 20th September, 1892, when she saved the lives of four local fishermen.

On the 16th August, 1894, she was launched together with the Augusta and they rescued many men from the local fishing fleet which had been caught in a storm.

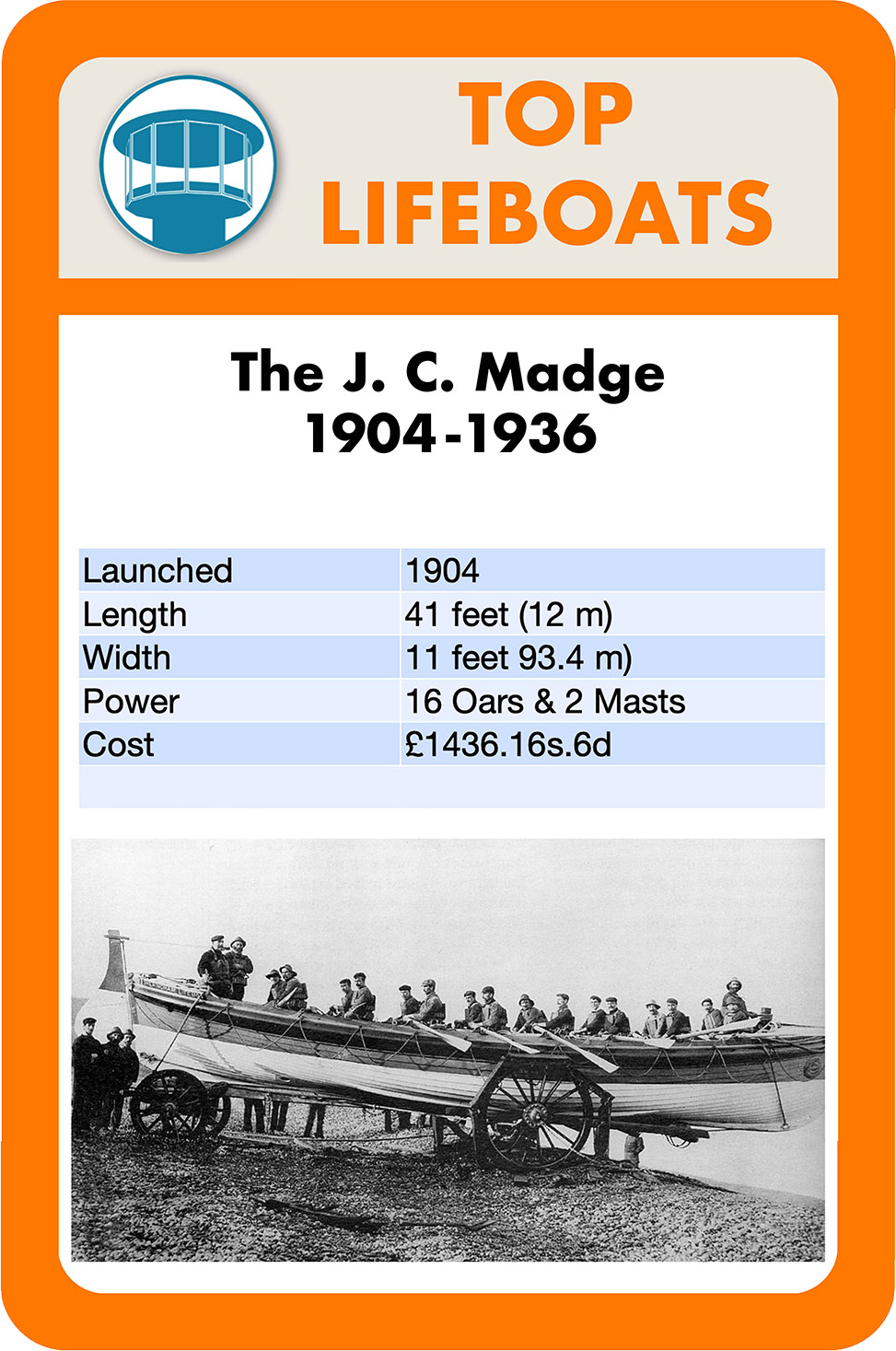

The J.C.Madge

1904-1936

The J.C. Madge is the oldest lifeboat that you can see in Sheringham Museum and is the largest lifeboat to be powered only by oars and sails. She’s not self righting.

She was built at the Thames Iron Works and Shipbuilding Company in London. She was sailed around to Sheringham with the men resting overnight at Harwich and Great Yarmouth. She had her own launch carriage. She was launched 34 times and saved 58 lives.

For each launch, men would attach heavy ropes to the carriage and then a team of 30 or more would drag the boat down to the sea. When she came to land, a winch operated by men would pull her back up the shore to the boat shed. Her crew had to clamber across the golf course in all weathers to launch her, in fact tales were told of crew falling into hidden bunkers on snowy nights!

Her shed was at the Old Hythe at the western end of the Prom, in front of the Golf Course.

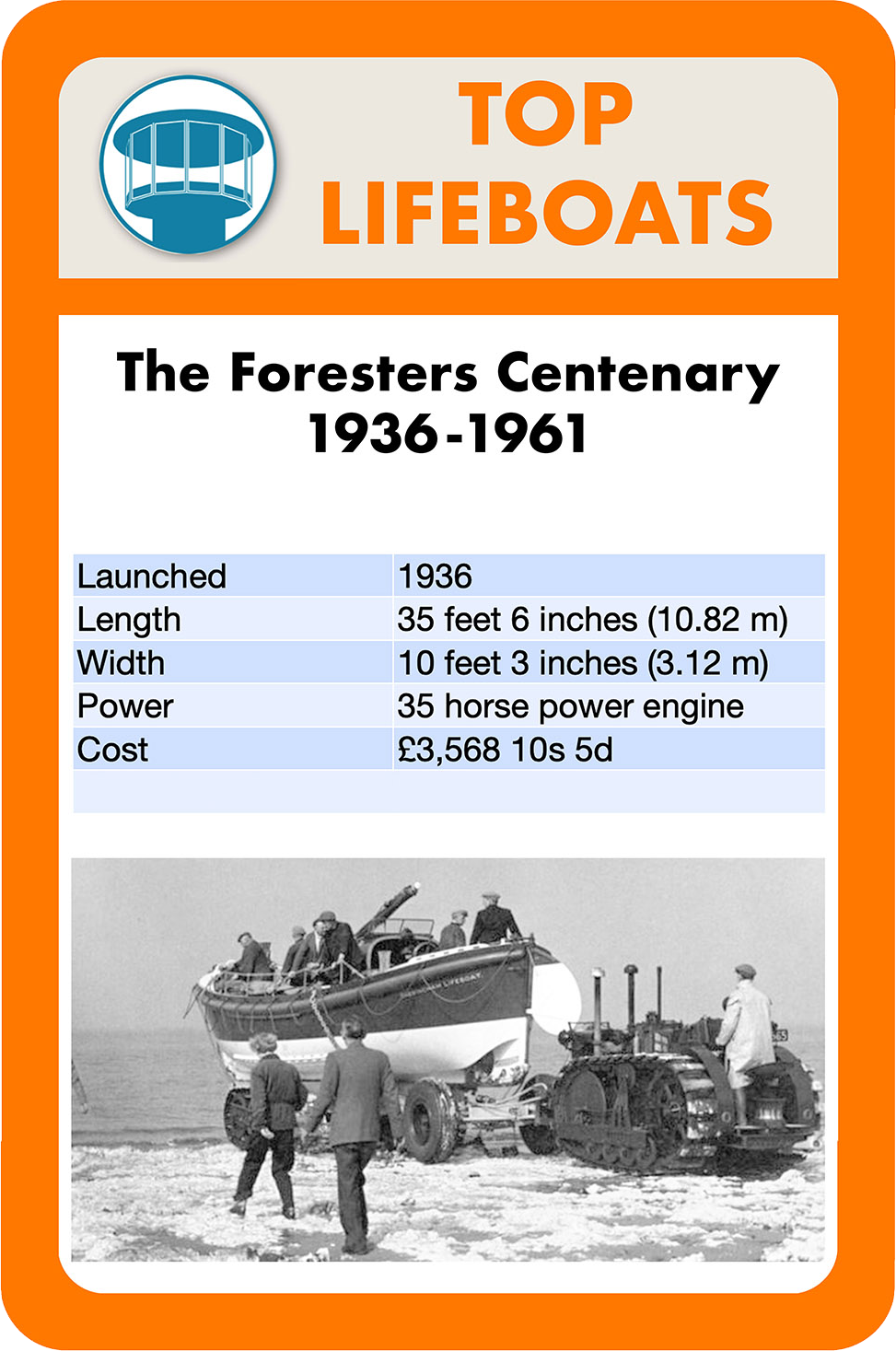

The Foresters Centenary

1936 – 1961

This Liverpool class lifeboat was in use for 25 years. The design of the Foresters Centenary was very stable, but she wasn’t self righting. She was Sheringham’s first motor lifeboat had a 35 horse power petrol engine but in case the engine went wrong, she did have sails.

The Ancient Order of Foresters Friendly Society donated her to the RNLI. During her 129 launches at Sheringham, she saved 82 lives. Her new boathouse was built at the end of the West Prom in 1937, and it still houses today’s lifeboat.

(You can visit the lifeboat house in the summer if you walk west along the prom as far as you can go.)

So, the crew could run along the prom if there was a Shout, to save them scrabbling across the golf course. The Foresters Centenary was the Lifeboat in service during World War 2 and rescued more airmen than any other RNLI Lifeboat in the country.

Her home now is Sheringham Museum and there she can rest and welcome visitors.

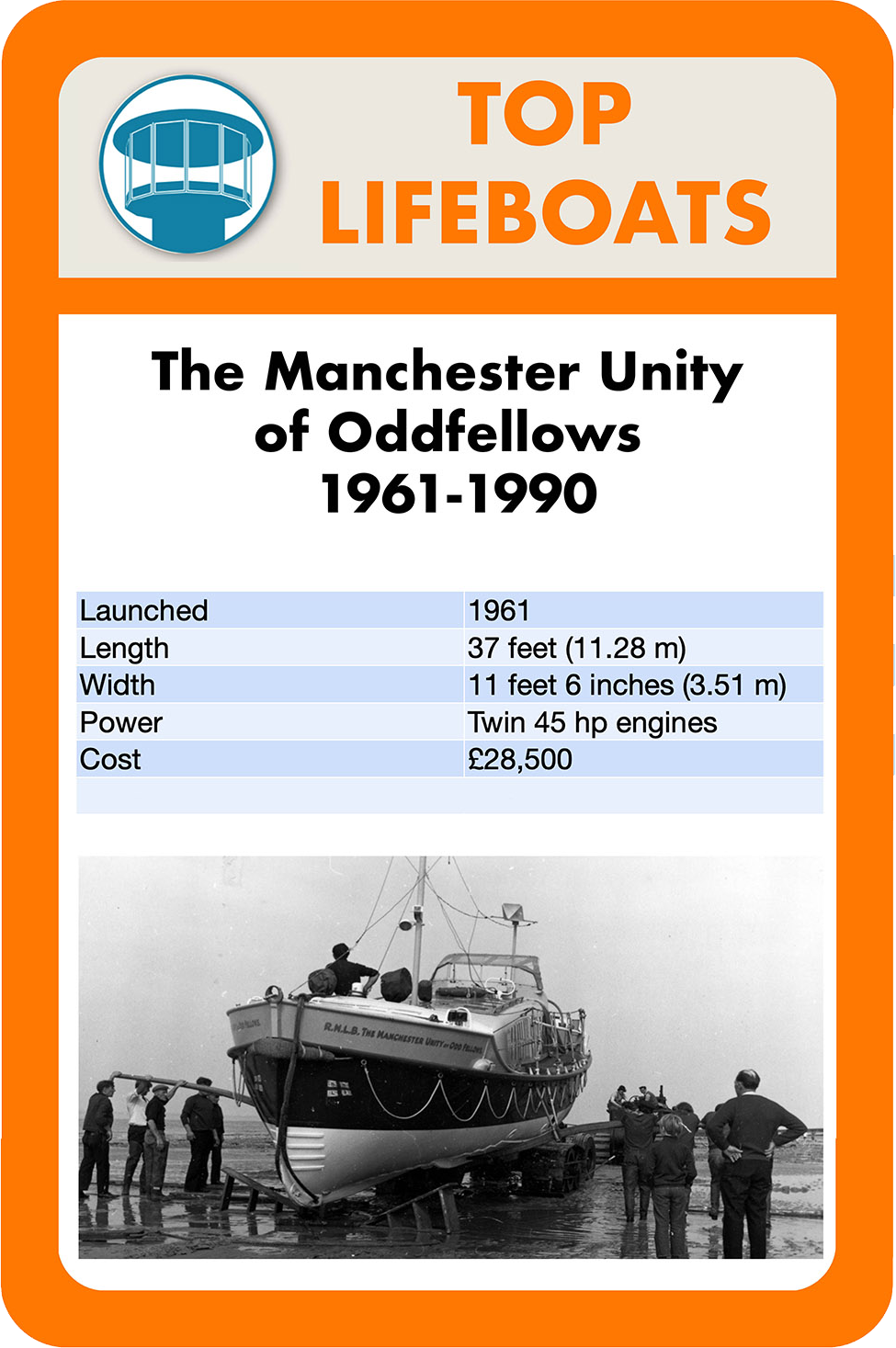

The Manchester Unity of Oddfellows

1961-1990

The Manchester Unity of Oddfellows was Sheringham’s longest serving offshore motor lifeboat. Built in Sussex, she is the really big boat that you see when you enter the Museum boat hall.

She’s 37 feet long and 11 feet wide and if she turns over in the sea, she automatically rights herself. From the bottom of the keel to the top of the cabin she is as tall as the prehistoric mammoth whose fossil was found in the West Runton cliffs.

For 29 years she served Sheringham and launched 127 times, saving 134 lives..

The Atlantic 75 Manchester Unity of Oddfellows

1994- 2008

Sheringham Lifeboat Station had the very first of the Atlantic 75 lifeboats, a rigid inflatable boat donated again by the generous Oddfellows.

Built in Cowes, on the Isle of Wight, she was much smaller than Sheringham’s previous lifeboats. She was the fastest of the RNLI boats at that time, with twin outboard engines. At 24 feet long and 8 feet wide and self righting, the Atlantic 75 only needed 3 crew for a very bumpy ride in rough weather.

It was much quicker to launch these boats, using a special tractor and a carriage. Thanks to the Manchester Unity of Oddfellows, you can visit this very boat in Sheringham Museum. When she retired and was put up for sale, the Oddfellows paid for her again and gave her to the Museum. We had to build a new floor to put her in!

Lifeboat Crew Equipment – Then and Now

Protective clothing

For nearly 200 years lifeboat crews up and down the country have had to launch their boats in the worst of weathers. To face the toughest conditions they have always needed the right clothing. The helmsman here is wearing yellow oilskins, a kapok lifejacket and a sou’wester.

Outer layers

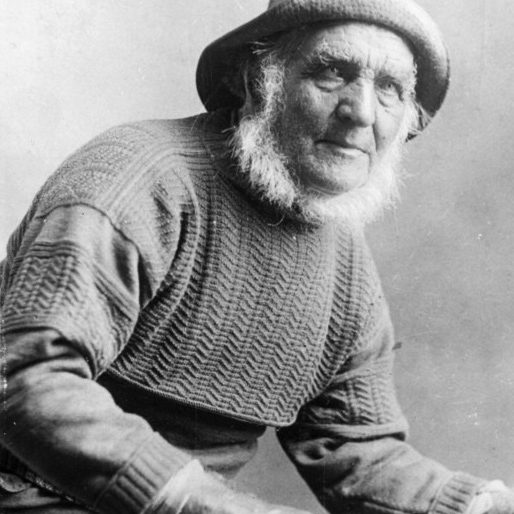

Apart from oilskins (waterproof coats and trousers), sou’westers (waterproof hats) and long leather boots early lifeboat crews in Sheringham wore ganseys. These woolly fishermen’s jumpers kept crews warm and dry.

Cork Lifejackets

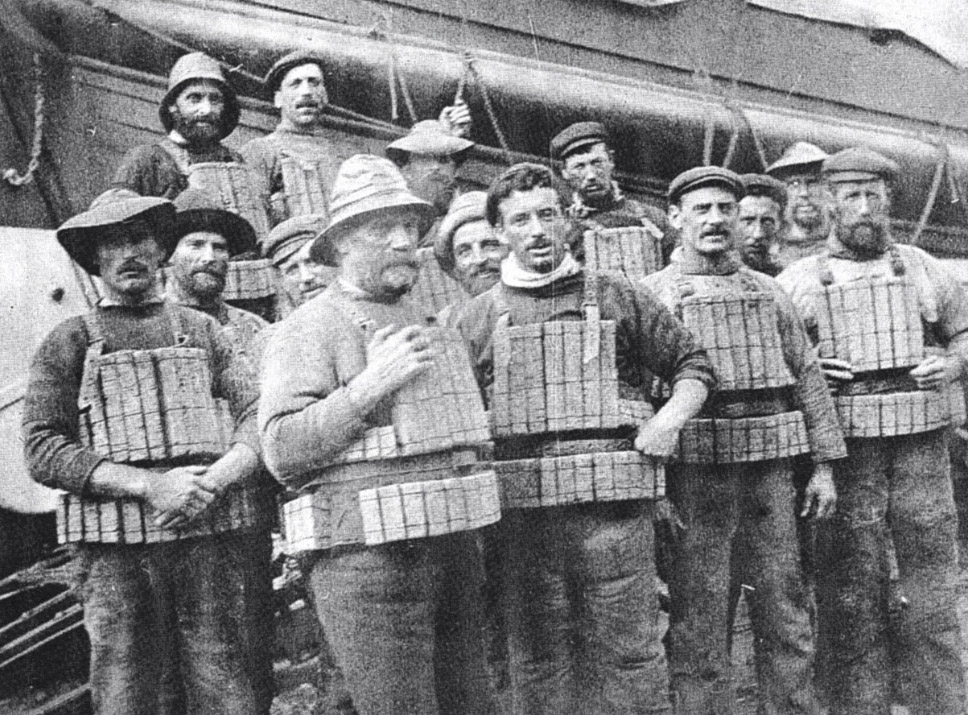

When you’re out at sea it is always best to wear a lifejacket. The first lifejacket used by the RNLI was the cork lifejacket invented in 1854 by the RNLI Inspector Captain Ward. This was the first ever lifejacket issued to lifeboat crews in Sheringham.

The lifejacket invented by Captain Ward was made of narrow strips of cork, circular in shape. When fitted together they were sewn into a strong canvas vest. They were hard wearing, flexible and floated well, and the crews liked them.

Why do you think that the lifejackets had to be flexible? In the 19th century the lifeboat crews had to be able to move comfortably when both launching and rowing the lifeboat. Take a look at this photograph. All the lifeboat crew are wearing cork lifejackets.

Today’s lifejackets

By the 1990s separate lifejackets for different lifesaving disciplines were introduced. The bulkier gear of all weather lifeboat crews meant they needed a more compact lifejacket, which inflated automatically on hitting the water using a built-in gas canister. Inshore crews, who enter the water much more frequently, got a bigger lifejacket with built-in buoyancy.They have lights, flare pockets, spray hoods, whistles, and safety lines and are flexible. When they are inflated, they keep the wearer’s head clear of the water.

By the 1990s separate lifejackets for different lifesaving disciplines were introduced. The bulkier gear of all weather lifeboat crews meant they needed a more compact lifejacket, which inflated automatically on hitting the water using a built-in gas canister. Inshore crews, who enter the water much more frequently, got a bigger lifejacket with built-in buoyancy.They have lights, flare pockets, spray hoods, whistles, and safety lines and are flexible. When they are inflated, they keep the wearer’s head clear of the water.

Kapok Lifejackets

By the beginning of the 20th Century Kapok was used to replace the old cork lifejackets. Kapok is a fine, cotton-like material which is used for stuffing cushions and toys.

Kapok is a natural substance and comes from gigantic tropical trees. The fibres are hollow and oily – which makes them light and nonabsorbent to water. The kapok life jackets were made of canvas pockets which were then filled with kapok.

These new life jackets had a supporting force that was stronger by 3½ times to that of cork. But, at the beginning there were many problems in designing the kapok lifejacket, and many lifeboat crews would not wear them, saying ‘they would rather drown than wear them’. RNLI crews used kapok lifejackets for 70 years once the design was sorted out.

Lifeboatmen wearing kapok lifejackets by the J C Madge

Activity

Design your own Gansey

Each fishing family would have their own gansey pattern which would have been inspired by their own town, family, weather or even everyday objects.

You can find lots of gansey examples online. Have a go at designing your own gansey.

Click on the image to make it larger on your screen.

Renewable energy

The Sheringham Shoal

Renewable energy is sustainable energy and it is made from resources that nature can replace. These are things like wind, water and sunshine. Most renewable energy sources are clean energy and they don’t produce harmful gases that cause pollution and climate change.

In the sea, just off Sheringham, there is a wind farm. Click on this video to see the turbines that produce electricity that we use in our homes.

On a clear and breezy day it’s great fun to look out from the beach at Sheringham and see the wind turbines spinning.

The Sheringham Shoal gets its name because it’s built on a shoal. A ‘shoal’ is a raised piece of land in the sea that is only covered by shallow water.

What is Renewable Energy?

Originally, the earth’s atmosphere had lots of carbon dioxide and very little oxygen; it was a climate where humans could not survive. Over many millions of years, plants have been using energy from sunlight and carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to grow, at the same time producing both the oxygen that we need to breathe and a more gentle climate.

The carbon they extracted is now locked away as coal, gas and oil, all non-renewable. When we burn them, we put that carbon dioxide back in the atmosphere. Too much of it is damaging our climate.

Forms of renewable energy

Renewable Energy is energy we can collect from around us without destroying our environment. We can collect energy from the wind, from sunlight and from flowing water.

Let’s find out more about each of these.

Wind

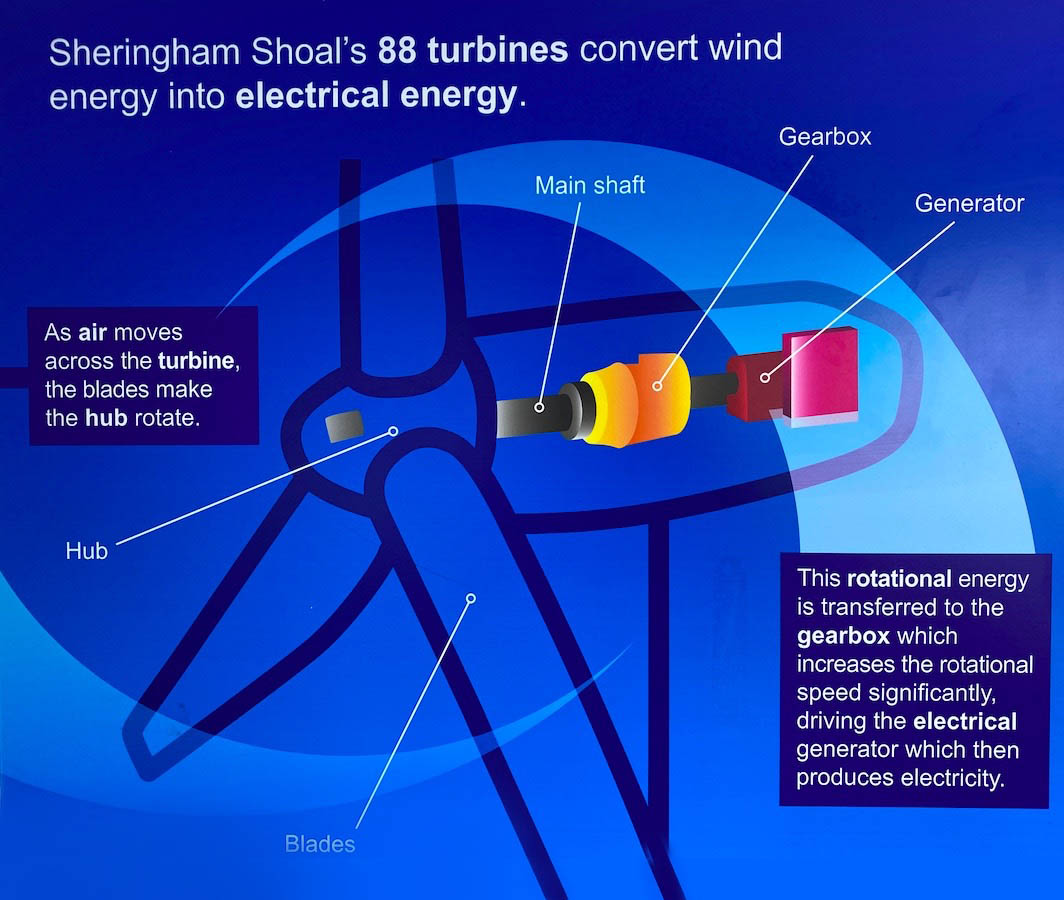

How does a turbine work?

A wind turbine is a very complicated piece of machinery. It has more than 8000 parts. How do you build such a big and complicated piece of machinery out at sea. Well it’s a bit like building a model from a kit. There are four main sections that need to be transported out to sea.

- The base (seat)

- The tower sections

- The nacelle (casing) which holds the generator

- The turbine blades

When all the parts get to the right place, special ships which can raise themselves out of the water are used to provide a platform where all the pieces can be put together.

Once in place the turbine is tested and when it goes into production green energy is made.

Click on the image to the right to make it larger.

Think about all the ways that you use electricity in a day from the moment that you get up and switch on a light to powering your television, computer, mobile phone, washing machine, kettle and perhaps your car.

If you’d like to find out more then come along to the Wind Farm Room Sheringham Museum!

Find out more!

If you would like to find out more about the Sheringham Shoal you can come along to the Sheringham Museum where we have a ‘Wind Farm Room’.

You can watch videos that explain more about how the wind turbines are built out at sea, how they work and how wind energy has been an important sustainable resource for hundreds of years in Norfolk.

- The blades turn. Did you know that the blades can rotate in their sockets to suit the windspeed?

- The hub spins and as the shaft turns energy is transferred to the gearbox

- The gearbox uses cogs to increase the speed of a magnet which spins inside a coil of wire and this generates the electricity

- Each of the turbines on the Sheringham Shoal is connected to a power cable which comes ashore at Weybourne

- The power then travels 21.6 km along an underground cable to a substation at Salle, near to Cawston, then down to Norwich and eventually to the National Grid

Sheringham Shoal – Fascinating Facts

The 317MW (mega watt) Sheringham Shoal Offshore Wind Farm is:

- Between 17 and 23 kilometres off the coast of North Norfolk

- Covers an area of approximately 35 square kilometres

- There are currently 88 wind turbines

- The turbines generate around 1.1 TWh (terrawatt hours) of green energy every year

- They provide enough clean energy to power almost 220,000 British homes

- Turbine blade length 52m (170 feet)

- Turbine tower height 80m (262 feet)

Solar Power

Electricity can be made from another natural resource – the sun! The sun’s light can be captured by solar cells to make electricity. The sun shines on the solar panel and the cells in the panel turn that light into electricity.

There are solar panels all around Sheringham. They are on house roofs and even in some fields. The big solar installations in the fields are called ‘solar farms’ and they make electricity that goes into the National Grid.

Water Power

Water can be used in a variety of ways to make electricity. There’s hydroelectric power where power is produced with moving water. Many of the UK’s hydroelectric power stations are in Scotland and Wales.

They work by releasing fast flowing water from a dam high above the turbines. The water flows down through pipes and turns turbine blades, similar to the turbines at the Sheringham Shoal.

As the blades spin they generate electricity. It is a good renewable way of making power.

The dam at Cruachan Power Station

Cruachan Reservoir, James Hearton, CC BY-SA 2.0

Tidal Energy

The sea is an amazing resource and as the tides come in and out we can use the power of the sea to generate electricity.

This can be done in three ways. Tidal streams, barrages and tidal lagoons.

The picture here is the most powerful tidal turbine in the sea near Orkney. It’s called the Orbital O2 and it should be able to provide electricity for 2000 homes for the next 15 years.

Why don’t you do some investigating to find out more about tidal power, solar power and wind power?

Green energy is our future.

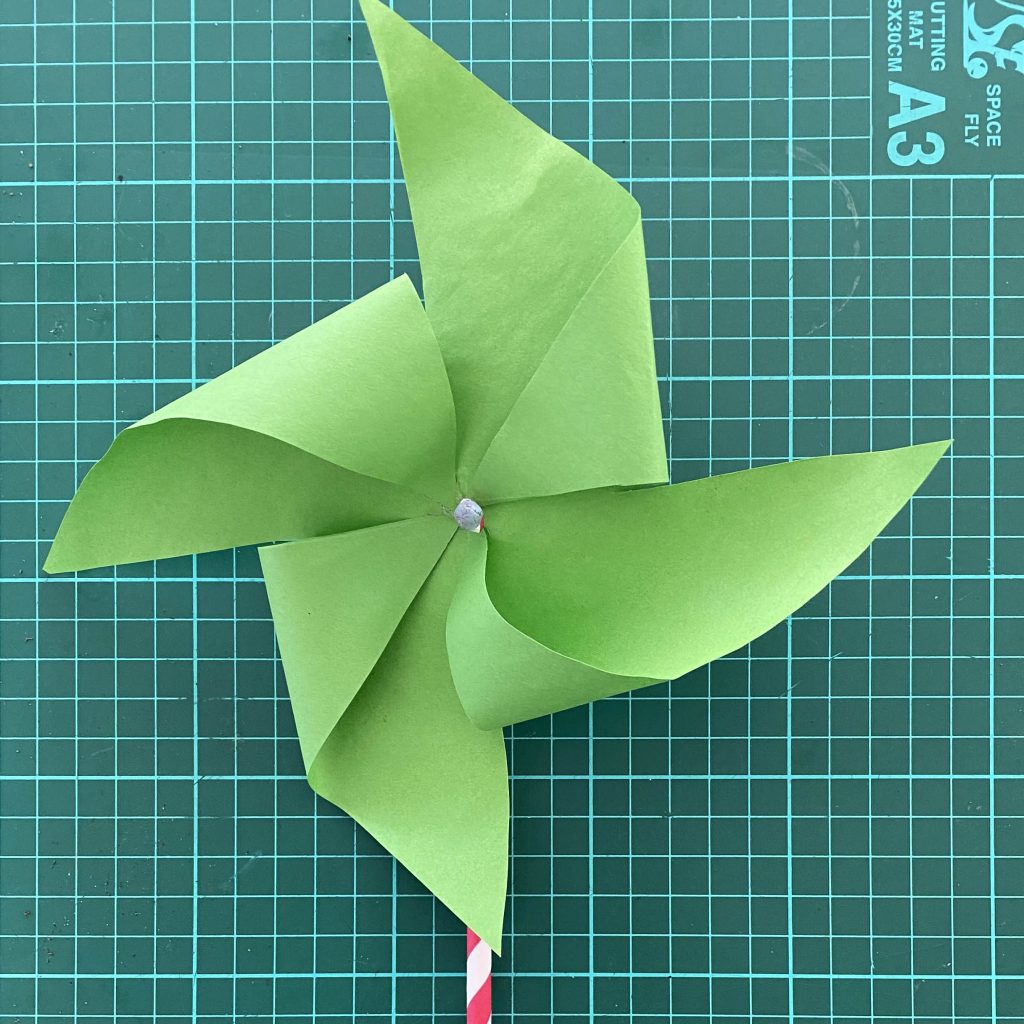

Activity

Make a windmill

To make a windmill you will need:

- A paper straw

- Scissors

- A glue stick

- Two tiny balls of Blu tack

- An ordinary paper clip

- A 16cm square of coloured paper

Let’s get started!

- Fold your 16 cm square diagonally corner to corner – this will make it look like a triangle. Then do it again folding from the other corner.

- Unfold your square and you will see that the creases in the paper look like an X

- Cut half way along the 4 fold marks

- Fold each point into the centre of your square and glue it in place

- Now take your straw and carefully cut two tiny circles from the end of the straw. Push these into the Blu tack. These are going to make spacers so that your windmill will spin.

- Now take your paper clip and unfold one arm of the paperclip so that it stick out. Now place the clip into the straw.

- Next you put on your first spacer

- Carefully make a small hole in the centre of your windmill with the tip of your scissors. You can get a grown up to help you.

- Put your windmill onto the paperclip and then put on the last spacer so that the point of the paperclip is covered safely.

- Now you’ve made your windmill it’s time to take it outside in the breeze for a spin